Whatever

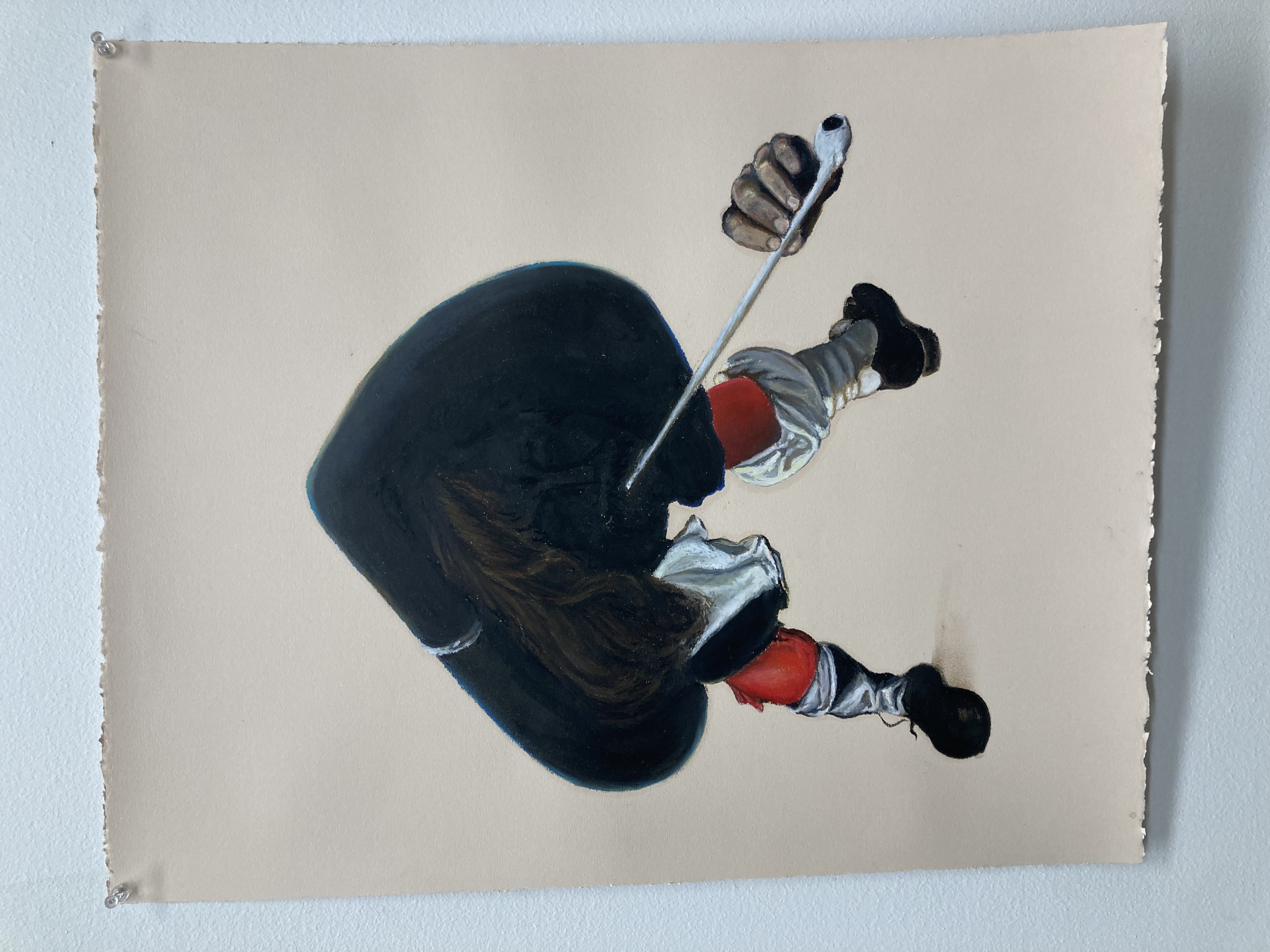

Warpaint no. 1, Oil pastel on paper, 2023

This picture samples paintings about being at war, being a painter, and being a drunk. I plan to make more like it, and I ended up making it because I was led to it by a painting that samples paintings about death and revelry and imagined lands that I’m still working on. Immediately after finishing this picture, I started making drawings based on prepatory sketches for historical paintings and prints about apocalypse, madness, war, piousness, and dentistry.

The left foot in this painting comes from one of the strangest and most unpleasant paintings I know of, Soldiers Plundering a Farm by Sebastiaen Vrancx, who was both an unremarkable soldier and an important painter.

Certainly part of the reason it feels that way is because of how long I have looked at it, but you have to do that this painting. The strangeness reveals itself over time because so much is unintentional, accumulated, or sublimated.

The painting, was made to have a very legible meaning. That you would look at it and see the villany of the soldiers as they maurauded the countryside under the lightest pretense that, at some point, they would fight in the war they were hired to fight, hopefully on the right side. Among the miliary scenes of Sebastiaen Vrancx, this painting stands out in its scale and plot. Rather than depicting the grand sweep of an important battle between consequential generals, we have an anonymous farmhouse belonging to civilians, possibly citizens of the same empires as some of the soldestka happily slaughtering them. And everyone looks more like a cartoon than anything in Vrancx’s paintings of war. It’s closer to his genre work, of daily life or allegorical scenes. The tendency of classical Dutch painters to depict humans as puglike wads of bleached flesh has always fascinated and disguested me. It’s like they are simultaneously criticizing humans for committing the crime of being alive and apologizing for their own complicity.

This painting is a sitcom. Look at the set framing and even the lighting. Dutch painters at this time, including Vrancx, were very aware of optical perspective, but applied its rules selectively. This has none of the excruciating “accuracy” of a still life filled with the spoils of empire. Narrative distorted the lens, placed characters in explicable rather than physical space, removed the fourth wall of the set so the audience can see everyone doing all the significant things, wearing all the signifying articles of clothing.

This painting is a cartoon. The colors, the edges, the level of detail. These are images to illustrate action. But for someone like Vrancx, a cartoon was a prepartory sketch, a diagram describing who goes where and what the edges of things are. To be more than that, to be a painting, he had to at least gesture at the incidental details of “realism” (a nonexistent term in the 1660s). The dull metallic sheen of the central soldier’s helmet, the logs of firewood stashed away in the rafters. Perhaps the model for the man about to be struck down was a local farmer Vrancx broke bread with. Maybe he was someone he killed or watched die during his time as a soldier, maybe he was made up from Vrancx’s own latent mental space of Dutch faces.

There’s so much wrong and weird with this painting, but it still works. This happened, this is happening, this will happen again. How hard do we need to squint to see the official narrative, that to be a soldier means this or that, that war is necessary? How long can we hold one eye shut with that in mind until we let go and just see a bunch of young unattached men with weapons, killing and plundering people who don’t have them because they were busy raising crops and children?

And maybe it – the attempt to communicate horror – works better because it’s so blobby and awkward? I have no idea how this appears to a normal person – I’m at the point where the bawling toddler bawling, alone in the middle of incomprehensible chaos, has become my a reaction meme in my own mind for various tragedies, big and small.

But I think the ugliness is part of what makes it work. The unfathomable unsexiness of it. The visual bluntness of the weapons, the soldier’s dark robes outlined as if being explained to a child. And, as modern viewers, all of that just runs headlong into the vague, historically freighted sense of this as old valuable “art”. It’s a Dutch painting by a famous painter from the 17th Century! How much more art can you get than that? We have to undress it, strip the period costumes and ineffably-specific aesthetic turns, and imagine that it once was a window into a way that humans lived, perhaps a very smudged one, but a window still. From our distance the whole aesthetic of its era blurs together, but if you’re looking at at the calm, well-lit rooms of Vermeer or the precise hedonism of Weenix, and you remember this painting, the toddler’s wail breaks the refined mood like a siren in the distance.

Speaking of Vermeer, that’s the back leg. Vermeer’s (likely) actual use of actual optics gives his orange stocking not just a sublime luminosity, but also, you know, the shape of a human leg. And I say it’s his because it’s not just from his painting, but because it’s his own painting of his own leg in The Art of Painting.

The domestic scene that painting depicts is about as far from the plundered farmhouse as you can get, conceptually, without leaving the Dutch “golden age” entirely. I wonder whose stocking cost more, and who paid for the one the soldier is wearing.

And speaking of wailing toddlers, the black hat, pipe, hair, and ghost face are from Jan Steen. Specifically his painting, As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young, and specifically the earlier, smaller version.

There’s another toddler in this milieu, swabbing up life-shaping trauma like his playmate in the farmhouse, but having a lot more fun as he does. He’s part of the “young” of the title – the impressionable youth, at risk from the merriment of the adults. Steen had a grand career of painting, with deep and experienced relish, rooms full of lowlifes having an excellent time doing everything they aren’t supposed to, usually putting himself right in the middle. His paintings are kind of anti-still-lives. Some nice objects that signify material wealth are getting absolutely thrashed in this very painting. Vrancx’s people look messed up, but like Vrancx was still trying. When Steen exaggerates a subject’s features for some lost aesthetic meaning, they look like a goddamn alien. He painted – and one would assume got paid for – an aspirational interior scene of the family Gerrit Schouten, the owner of the Elephant brewery, in which his daughters are so willowy they look like praying mantises in period dress. I often wonder how he was ever sober enough to paint.

Generally, I’m averse to direct connections between the historical “meaning” of the paintings I’m looking at and the paintings I make because the temptation of “getting” it encourages you to look past the distortions. If any my paintings had a “point,” it would be what’s wrong with them when you compare them to the paintings they look like, not what’s “right.” There’s an engagement with paint-as-paint in still lives of this era that’s startlingly contemporary once you see it. Genre paintings, like the ones this picture has snipped pieces from, get distracted by plot and character. We can go from Vrancx to Vermeer to see the scope of how much seeing was considered important on the grand stage of life. And then, honking out an armpit fart version of Het Wilhelmus, here comes Steen, the drunken master with his own 4 a.m. wisdom.

Digging into these sitcom-cartoon-allegories full of fleshy, awkward people has built a dim, drafty theater in my mind. I’m sitting in the back of it, watching a play of manners in a language I don’t understand. Sometimes the sun will break through the window so realistically I feel the warmth and am suddenly aware of exactly how ripe the pears on the table are, the number of strands of hair out of place in the lead actress’s complex hairstyle. Sometimes soldiers or disease tear through and kill half the cast, and I can’t tell if the blood is real. The smell of old beer certainly is.

I don’t understand how Steen, Vermeer, and Vrancx’s scenes all existed at the same time as part of the same way of life, just like I don’t understand exactly how to fit life as a painter into the world we currently have.