Technological disobedience

This essay was originally published in a zine for an opening at the PCNA MFA design program in Portland, sometime around 2017. The rest of the details escape me!

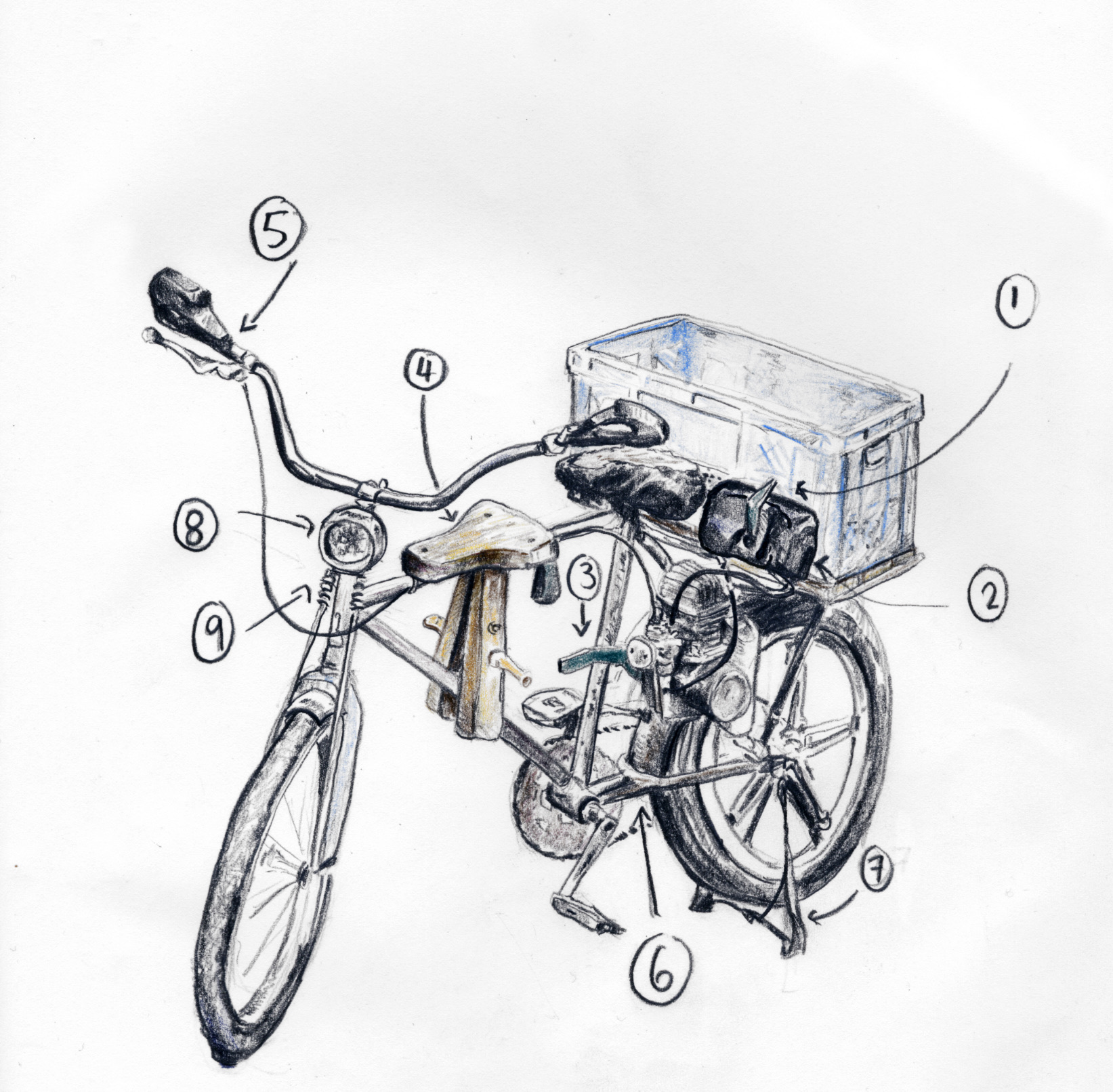

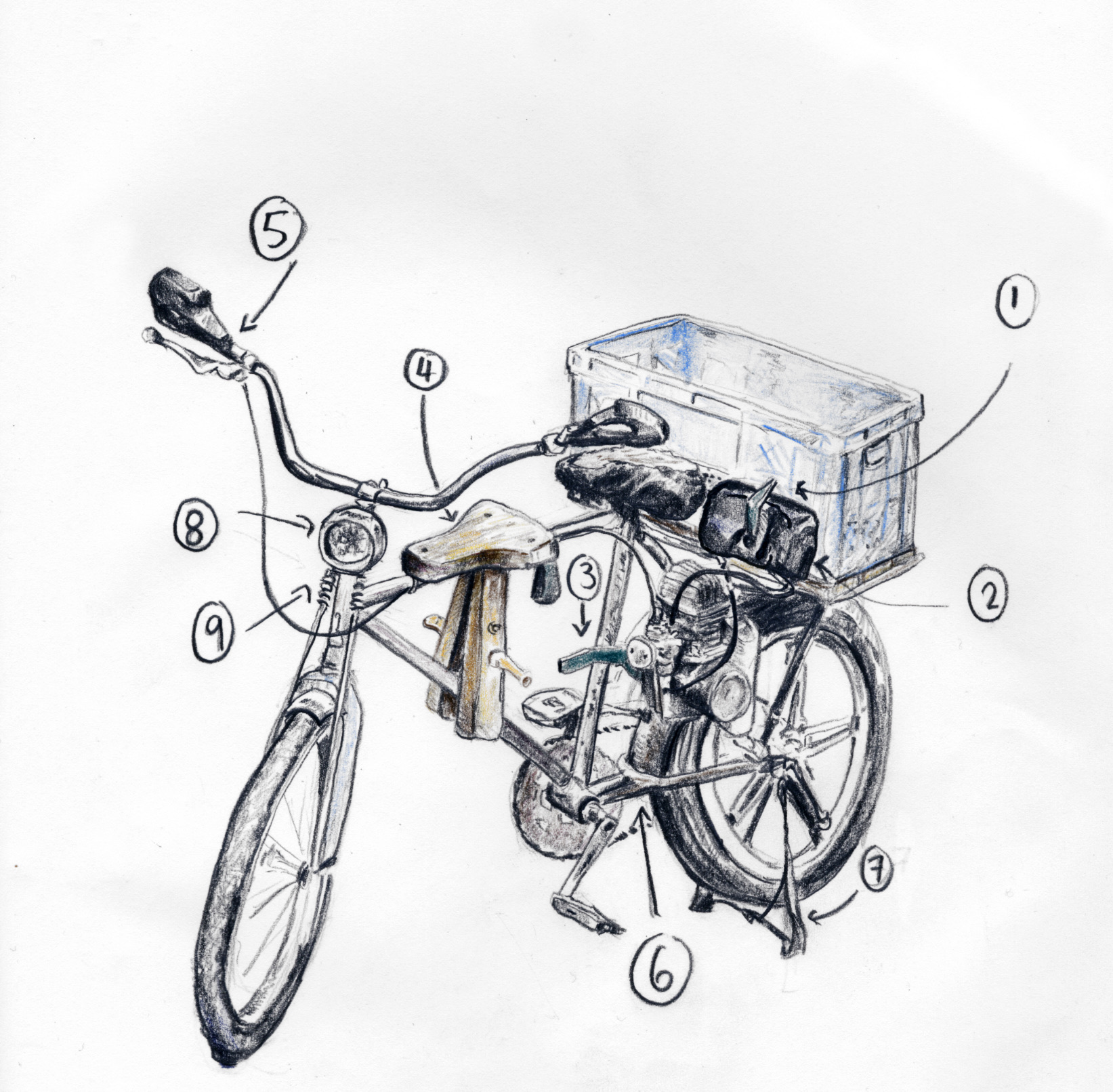

This is a rikimbili – one of the ubiquitous yet illegal motorized bicycle conversions in Cuba that form a unique part of the ad-hoc infrastructure of goods and services that run the island nation’s economy.

This is a rikimbili – one of the ubiquitous yet illegal motorized bicycle conversions in Cuba that form a unique part of the ad-hoc infrastructure of goods and services that run the island nation’s economy.

This Rikimbili

- Repurposed plastic crate used for food and supply delivery

- Gravity fed gas tank, mounted with a strap tied through the crate

- Handle for engaging the direct-drive transmission, which consists of pressing the motor’s driveshaft to the back wheel.

- Handmade second seat, likely out of palm wood. These seats are very common on all types of bicycles in Cuba. Note the foot pegs to accommodate children.

- Modern, ergonomic handlebars.

- The entire rear section had been rebuilt to make it possible to replace the back wheel with a motorcycle wheel.

- Handmade kickstand, welded and bolted from scrap metal.

- Brand new Chinese made LED headlamp

- Handmade shock absorbers.

This one was seen delivering food and supplies to a state-licensed tourist stop on the bus line between Havana and Cienfuegos. Though easier to spot within urban areas, one can still see rikimbilis transporting goods and passengers past the ever-present groups of commuters and travelers waiting in semi-official clusters on the side of the highway to catch a ride with any willing vehicle, whether it’s a tour bus or vintage taxi. The sounds of their unmuffled engines highlight gaps in transportation and urban planning and exemplify the hustle and ingenuity that Cuban citizens wield in the face of shortages, restrictions, and poverty.

The design and use of the rikimbili is irrevocably tied to the unique material, political, and economic circumstances in Cuba. Though travel to the state has been legal for US citizens since 2015, (update: not anymore) the US’s controversial trade embargo remains in place. While the terms and history of the embargo are complex, but it has had an undeniable impact on daily life in Cuba. However, there are many more factors that have placed Cuba’s supply chain and economy in an ongoing state of crisis. Given the state’s enormous amount of control over the use and allocation of resources (and who has access to information about those decisions), government management can’t be discounted as a factor in Cuba’s economic issues in the last 50 years, even if the results can’t be clearly separated from the effects of foreign policy. However, there is no question that the fall of the Soviet Union was one of the most important contributing factors to Cuba’s current material circumstances. Trade agreements with the USSR had supplied the vast majority of consumer and industrial goods, as well as a significant amount of fuel and agricultural products. The abrupt dissolution of these agreements led to a period of economic constraint so severe, the government gave it an official, if euphemistic, name – “The Special Period in Time of Peace”. That period is over, and things are changing fast in Cuba, but current conditions are still heavily shaped by these historical forces.

In the absence of a functional supply chain, Cuban citizens have created a sort of social supply chain with its own set of standard practices and products, developed by tinkerers, engineers, and regular people over decades. During Período especial, the government recognized that conditions would require resourcefulness and released The Book for the Family. The now-classic book compiled international publications, including Popular Mechanics, featuring instructions for repairing home electronics, some medical reference, a guide to phytotherapy with indigenous plants, and instructions for improvising weapons. This was, in part, a condensation of knowledge from the military’s preparations for an American invasion that never came. Two years later, they released a second book to share the innovations that Cuban citizens had produced – Con Nuestros Propios Esfuerzos (“With Our Own Efforts”). Among its many recipes and products that spread throughout the Cuban design community, one of the most infamous was a recipe for turning grapefruit rind into a kind of steak.

These books were a formal recognition of the DIY culture of distribution, production, and maintenance that Cuban citizens developed to get through their daily lives. Products like chargers to restore single-use hearing aid batteries and gravity-powered engine starters are deeply integrated with the social fabric that requires, produces, and uses them. According to illustrator Edel Rodriguez, “Everything has to be hustled by connection, by someone you know or farmers. And most of it can’t be had by legal means.” This is a community design culture, driven by necessity, which disregards not just legal limitations but the very definitions of the products they work with.

While researching for his book on rikimbilis, Cuban artist and designer Ernesto Oroza coined the term “technological disobedience” to summarize “how Cubans acted in relation to technology.” He says they surpass not just the limits of their controlled economy, but the “authority” held by contemporary, manufactured objects. Oroza saw the emergence of the rikimbili as a socially designed object “like a milestone in the technical knowledge of Cubans during the crisis… and it represented many ideas. Especially the audacity to confront very complex technology and to risk one’s life by using a potentially lethal object.”

Oroza appears in a short documentary about his collection of Cuban inventions

His body of work and the concept of technological disobedience provide a rich lens through which to ask the questions of how design serves the needs of its intended audience, and the forms that a community’s response to crisis or pressure can take.

For example, community response to failing infrastructure in American cities like Detroit can be seen as further expressions of technological disobedience. When the bureaucratically-paralyzed water authority engaged in mass shutoffs of residential water, locals who could access or make water keys emerged as a new (paid) service in neighborhoods without water. While illegal, it can be seen as a legitimate response when institutions like golf courses kept their access to water despite owing hundreds of thousands of dollars, and when many accounts couldn’t be confirmed or tracked down to reinstate access once paid. The mass shutoffs were seen as a failure of oversight, not simply the inevitable result of private citizens failing to pay their bills. Similarly, there have been multiple projects by private citizens to create bus shelters or benches in response to the conditions of Detroit’s notoriously inadequate public transit system. The official response has not always been favorable, but solutions have yet to arrive through approved channels. As the material culture in Cuba demonstrates, communities will fill the gaps left by failing governance and infrastructure if pressed hard enough.